Keratoconus

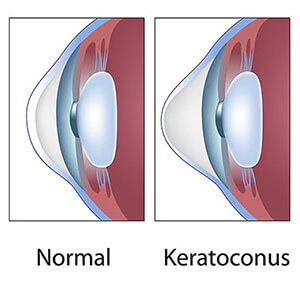

Keratoconus occurs when the cornea, which is the front, clear tissue of the eye similar to the windshield of a car, develops an abnormal thinning and irregular shape, causing distortion of light rays passing through it. This results in blurred vision that cannot be corrected with eyeglasses. The exact cause of keratoconus is unknown, although research suggests a genetic predisposition. The diagnosis is initially made during an eye exam when an irregular corneal curvature makes it impossible to correct vision to normal levels using eyeglass lenses. Sometimes, the corneal curvature is only mildly abnormal. This is often referred to as “forme fruste” keratoconus, which means a mild or incomplete form of the disease. It usually starts when patients are adolescents or young adults and continues into their thirties, at which point the progression of the disease either slows or stops. Males and females are equally affected. Signs of keratoconus are usually present in both eyes, although one eye may have much more involved than the other.

Keratoconus can be progressive in young patients, leading to an irregular outward protrusion of the cornea, known as ectasia. In advanced disease, this protrusion causes the cornea to develop a steepened “cone” shape when looked at from the side, which is why the disease was given the name keratoconus. Middle-aged patients with keratoconus, whose vision can be clearly corrected with contact lenses, are unlikely to develop more severe disease. Patients with advanced keratoconus can experience sudden episodes of painful corneal swelling, known as hydrops, that can lead to opacification and scarring of the cornea, causing permanent vision loss.

The treatment of keratoconus depends on its severity. For early or mild cases, eyeglasses may correct vision to levels that are sufficient for most normal activities, even though those patients may not see 20/20. When vision can no longer be adequately corrected with glasses, soft contact lenses, either spherical or more commonly toric contact lenses that correct astigmatism, are used. There are many specialized types of contact lenses to help people with keratoconus. Some combine soft and rigid lens materials. The vast majority, however, depend on rigid gas permeable contact lenses to achieve a vision that is good enough to carry out normal daily activities. When contact lenses can no longer provide adequate vision correction, surgical treatment is the next step.

Corneal Transplantation

The cornea is the clear, front surface of the eye on which contact lenses are worn. One can picture it as the windshield of the eye. In order to see clearly, light rays must pass easily through a clear cornea. When the cornea is damaged, cloudy, or has an irregular curvature, clear vision is not possible. Some corneal conditions can be treated with glasses or contact lenses. In some situations, however, a corneal transplant may become necessary. Because the cornea does not get its nutrients from blood vessels, it is not necessary to “find a match” in order to have a transplant. Our national eye bank system screens and scrutinizes every donor cornea to find the healthiest and most optimal ones for transplantation. Generally, there is no wait time.

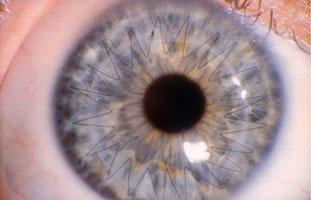

A Corneal Transplant is referred to as a Penetrating Keratoplasty (PKP) and involves removing the cloudy, diseased cornea, and replacing it with clear corneal tissue from an organ donor. This is sometimes called a “full-thickness transplant” because all the layers of the cornea are removed and replaced with new healthy donor tissue. A full-thickness corneal transplant generally becomes necessary in patients who have such excessive scarring and opacification, swelling, or irregular curvature/astigmatism that only a totally new cornea will help them.

Some corneal disorders, such as the genetic condition of Fuch’s Dystrophy, involve only one unhealthy layer of the cornea. Techniques that replace just the unhealthy layer of the cornea are evolving and are sometimes called “partial-thickness transplants”. An example of this is Descemet’s Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSEK) or Descemet’s Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK), two names that are used interchangeably.

DSEK is a form of corneal transplant surgery used to help patients who have poor vision due to corneal swelling caused by the absence or dysfunction of endothelial cells, the cells that line the inside surface of the cornea. These cells rest upon a membrane called Descemet’s membrane. The job of the endothelial cells is to act as a pump system in order to keep the cornea clear. When those cells do not work properly due to disease or damage, the cornea becomes swollen and cloudy. Surgery is a reasonable option when poor endothelial function causes corneal swelling that reduces vision to the point where normal activities become difficult.

DSEK involves the removal of the Descemet’s membrane and the poorly functioning endothelial cells. These are then replaced with Descemet’s membrane from an organ donor and healthy endothelium. Some patients who do not have Fuch’s dystrophy might, nevertheless, have a borderline endothelial function. In that case, any type of eye surgery, even cataract surgery that is performed perfectly, can result in corneal swelling that may eventually require DSEK.

Since DSEK requires a much smaller incision than full-thickness corneal transplant surgery, it has several advantages over the full-thickness procedure. Patients have a faster visual recovery time, less postoperative astigmatism, decreased the chance of rejection, and less risk of damage after eye trauma.

It is important to recognize that DSEK is not like cataract surgery; the patient must be aware that vision will take longer to become clear. There are no sutures to keep the transplant in place. Rather, an air bubble is placed into the eye to keep the transplanted tissue in place. Because air floats up, the patient must lie on his back or keep his head face-up as much as possible for the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery. This is usually the typical duration that the air bubble lasts. Also, since there are no sutures used to anchor the graft, there is a risk that the graft may “slip” or dislocate after surgery, in which case the surgeon will need to “re-float” the graft in the days or weeks after the surgery.

As with all surgeries, a corneal transplant carries the risk of infection and bleeding. Also, as is the case with any type of transplant, the risk of rejecting the donated tissue is a possibility. Any post-surgery trauma, such as falling or getting hit in the eye, can result in the opening of the wound since the donor tissue in a PKP is sewn into place with fine sutures. Astigmatism, or curvature that is not perfectly round and regular, is common after PK surgery. Consequently, some patients may need to wear a rigid gas-permeable contact lens after their transplant to correct astigmatism and optimize visual acuity. Transplants may also age and fail with time.

Patients must keep in mind that a transplant is more involved in surgery than cataract surgery. The postoperative course is more prolonged, with transplant patients seeing their doctor many times during the year after surgery to optimize visual outcomes. Achieving good, stable vision may take up to a year.

Pterygium

A large portion of a normal eye is covered by a clear, vascular tissue called the conjunctiva. That tissue is usually transparent and covers the white part of the eye, referred to as the sclera. When conjunctiva grows onto the cornea, the abnormal growth is called a Pterygium.

Pterygium is caused by excessive exposure to sunlight and wind irritation. It is more common in people who grew up in countries closer to the equator or who have spent significant time outdoors. The most common symptoms of pterygium include irritation, burning, foreign body sensation, tearing and light sensitivity. If the pterygium is very mild, frequent lubrication might adequately treat the symptoms and prevent increased growth. Severe cases can cause blurred vision, double vision or partial loss of vision. In moderate or severe cases, and especially if the pterygium is growing progressively, it should be surgically removed before it causes permanent scarring to the cornea and reduction in vision.